Abstract

An investigation into the themes behind Shakespearean dramatic characters who move to save blood (other than their own, or close kin) from being shed, or lives being lost, typically in mass suffering or injury or killings.

Introduction

In Shakespeare's plays, there are characters who sometimes intervene, or plan, to prevent bloodshed on a significant scale. The characters of interest here are generally neither peacemakers per se, nor pacifists; and generally ones who go beyond purely partisan interests.

And will, to save the blood on either side, Try fortune with him in a single fight.

The more realistic plays offer more general insight, so The Tempest's magic-wielding Prospero (who forsakes bloody revenge) is not included. Neither here considered are As You Like It's Rosalind (who creates a kind of marital peace, but the blood feuds are settled off-stage), nor The Merchant of Venice's Portia (only a single character's blood is saved, and Portia’s victory lacks justice, fairness and mercy). Neither considered are Troilus and Cressida's Hector advocating returning Helen and sparing defeated foes (a possible yet partisan fit), nor Romeo and Juliet's Prince, Nurse, Friar and Romeo himself, all of who have some shout in bloodsaving, yet whose motives appear counterweighted, compromised or opaque. Nor will characters who appear to have consistent pacifist or bloodshed-averse views be considered here (like Virgilia in Coriolanus). These tend to be untested characters (pacifism is awkward to be absolute in).

Verona's civil broils and Milan's coup are significant here, however, in broaching Shakespeare's concerns with civil war and conflict within kin groups.

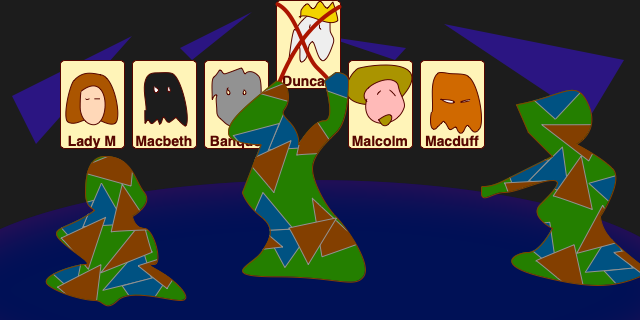

To illustrate this theme, the following characters will be examined: Edmund of Langley Duke of York (Richard II); Hamlet, Prince of Denmark (Hamlet); Titus Andronicus; and Pericles. I will also explain why a few characters (like Prince Henry in the quote above) cannot reasonably be counted as bloodsavers.

Pericles: perilous playboy or humanitarian hero?

Pericles, Prince of Tyre is a play concerned with good and bad government. Pericles endangers his own population by recklessly seeking the daughter of powerful Antiochus as a bride.

When all, for mine, if I may call offence, Must feel war's blow, who spares not innocence:

But in recompense, almost immediately relieves famine in Tharsus with purpose-brought grain, for which he largely wants only friendly relations and use of a port.

Pericles' attitudes to his subjects and subordinates is ambiguous. In A2s1, fishermen pity Pericles’ lost crew whose fate he seems oblivious to, though he may be half-dead with cold. While in A3s1, Pericles agrees to appease sailors’ superstitions and tosses his apparently dead queen overboard to save lives, though a fear of mutiny is also a likely motivation.

Another candidate bloodsaver in the play by vocation and practice is lordly physician Cerimon, who seems to attract honest admiration for good works (and a good work ethic).

I held it ever,

Virtue and cunning were endowments greater,

Than nobleness and riches”

Pericles fears the bloodbath that could be visited on his subjects/countryfolk (by Antiochus) and takes indirect means to avoid it. Yet later, under oath to goddess Diana says he was frighted from his country. Frighted for himself, his subjects, or both?

Hamlet: Denmark in Danger

Hamlet is Shakespeare's great play about Communication. Intriguingly, for all of Prince Hamlet's soliloquies, we still have to guess about a great deal of his motivation. From early in the play, we learn of enemies without and divisions within Denmark. A sizable number of Danes appear happy that usurper-King Claudius is hosting drunken revels rather than making them go off and wage war against formidable foes in the cold shores of the Baltic. Under Hamlet's cloak of madness, he may be settling scores (Polonius) or trying to repel/entreat others to a place of safety (Ophelia).

The play's foreshadowings are a much more reliable guide to its ending than Hamlet's musings. For example, in A2s2 the player’s speech features the destruction of Troy in flames and blood. In A3s1 Claudius smells danger.

But in case you missed all this, it is spelt out by a minor character:

The cease of majesty Does not alone; but, like a gulf, doth draw What’s near it, with it: it is a massy wheel, Fix’d on the summit of the highest mount, To whose huge spokes ten thousand lesser things Are mortis’d and adjoin’d; which, when it falls, Each small annexment, petty consequence, Attends the boist’rous ruin. Never alone Did the king sigh, but with a general groan.

Hamlet learns that thousands may die battling over a patch of land:

I see The imminent death of twenty thousand men,

By A4s5, Queen Gertrude fears some great amiss

and King Claudius fears the resentful people led by Laertes, drawn home by father’s death, as if people should choose their own king. On the other hand, in A5s2 Hamlet relates with relish how he sealed the fate of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, and pleads diminished responsibility to Laertes.

On the balance of probabilities within the text of the play, Hamlet forsees how enacting his revenge against Claudius will lead to bloodshed. On this reading, Hamlet's struggle to hold a King to justice can be read as an attempt to take the least bloody path, the means by which Gertrude, Ophelia, Laertes and others deemed not guilty will be spared (interestingly, Hamlet seems to regard Horatio as both valuable and expendable, ironically as it transpires). Shakespeare turns our attention to systems, to question why the rule of law does not apply for regal power with royal prerogative, to effectively propose election. But… do we really believe Hamlet's protestations that he does not value his own life? And how much does Hamlet really value other lives?

Henry V: premeditated war criminal

See above quote when Henry was a Prince. In Henry V A1s1, Henry protests his care not to shed blood, but it is clearly a pretence. See his father’s advice in the previous play. We later see his manipulation of traitors and mercy. Henry’s threat to French king, and particular to Harfleur, are chilling, horrifying, indeed terrorism. While soldiers before battle tell it like it is. Henry V is not a bloodsaver, though we see him pose as one when it suits.

Titus Andronicus: oops

It might seem strange to view Titus, a blood-shedding 40-year warrior for Imperial Rome, a sacrificer of a prisoner and murderer of his own son on his return, as a bloodsaver, but consider this. The homecoming warrior is both weary of blood and power but not honour “Give me a staff of honour for mine age” (A1s1), arrives unprepared for Roman politics at a wave of civil strife which immediately threatens to settle succession by open civil war. Titus (why does Rome keep repeating the mistake of electing victorious generals in Shakespeare’s plays?) is patently unsuited for civil office, unlike his diplomatic brother Marcus, and foists the even less suitable prince Saturninus on Rome, in apparent attempt to save blood on the streets.

This shows the sometimes disastrous side of blood-saving when it fails to treat the underlying problems or address politics maturely and responsibly. The younger princely brother Bassianus, already engaged to Titus’ daughter Lavinia, was the safer choice of Emperor, but whether through haste, respect for primogeniture or another reason, Titus makes this bad choice which sets the rest of the play on a tragic course. If Saturninus failed to accept Bassianus’ ascent, then likely the combined supporters of Titus, Marcus and Bassianus would have decisively prevailed in the civil conflict without weakening Rome as much as electing Saturninus does.

Undoubtedly Titus' character changes over the course of the play, distracted by grief and horror if not true repentance. When Marcus kills a fly, Titus is enraged by this tyranny over the innocent (and may not that fly have a mother and a father?), until Marcus denies the fly’s innocence. Perhaps there is a sense of Titus, so long the enforcer of Rome's 'Might is Right' imperial policing, failing to empathise with the innocent until the atrocity inflicted upon his daughter Lavinia finally (and far too late) opens his eyes, even to the point that flies might have rights.

Edmund of Langley Duke of York: the honourable exception?

When Shakespeare's dramatic projects want to stress an attribute common in a class of people, the playwright typically inserts an exception somewhere to emphasize what is the norm. Therefore Cressida is unfaithful, even though female characters are normally faithful. Prolix characters are generally politically inept, yet Gonzalo is astute. This is a powerful way of challenging stereotypes and emphasising the individual agency of characters, but also of judging social classes (the odd good king does not detract from Shakespeare's devastating critique of hereditary monarchy).

Most peace-making attempts fail in histories and tragedies (Edmund York may be an exception, but only a postponement). So we come to Richard II, and another looming civil war.

A number of characters, including the principal contenders for the throne, King Richard II and his cousin Henry (Hereford/Lancaster) Bolingbroke, make protestations about how they deeply care to spare the blood of subjects. Some notable quotes on this theme:

And for our eyes do hate the dire aspect Of civil wounds plough’d up with neighbours’ swords

Why have they dar’d to march So many miles upon her peaceful bosom; Frighting her pale-fac’d villages with war, And ostentation of despised arms?

It is noticeable that really only York uses humour in the play to defuse tension and (interspersed with more assertive passages) attempts to appear both relatively harmless and yet just.

If not, I’ll use the advantage of my power, And lay the summer’s dust with showers of blood, Rais’d from the wounds of slaughter’d Englishmen: The which, how far off from the mind of Bolingbroke It is, such crimson tempest should bedrench The fair green lap of King Richard’s land, My stooping duty tenderly shall show.

But Richard and Henry are quite happy to make such threats:

Armies of pestilence; and they shall strike Your children yet unborn, and unbegot… The purple testament of bleeding war; But ere the crown he looks for live in peace, Ten thousand bloody crowns of mothers’ sons Shall ill become the flower of England’s face; Change the complexion of her maid-pale peace To scarlet indignation, and bedew Her pastures’ grass with faithful English blood.

So no offer of single combat, then. A contrast is immediately provided by the gardeners (A3s4) who espouse a kind of biocracy, a view that a nation should be tended for all that live in it.

Richard II is the play which begins an arc of plays covering a bloody period in English, Irish, Scottish, Welsh and French history, a time of invasions, dynastic conflicts, political murder, civil war, massacres, various other war crimes and unnecessary infliction of mass suffering. We are given a foreshadowing of these future events:

And if you crown him, let me prophesy,— The blood of English shall manure the ground, And future ages groan for this foul act; Peace shall go sleep with Turks and infidels, And, in this seat of peace, tumultuous wars Shall kin with kin, and kind with kind confound; Disorder, horror, fear, and mutiny Shall here inhabit, and this land be call’d The field of Golgotha, and dead men’s sculls. O, if you rear this house against this house, It will the wofullest division prove, That ever fell upon this cursed earth

These likely effects are obvious enough to Carlisle, and indeed to York, who in striving to prevent them (for example, by remaining neutral in A2s3), perhaps only postpones them.

In the closing Act of the play, York privately states his allegiances to his wife, although the subtext is loyalty to the enduring state, rather than whoever currently sits on the throne:

To Bolingbroke are we sworn subjects now, Whose state and honour I for aye allow.

and immediately has cause to demonstrate such allegiance. On discovering their son Aumerle’s plotted treachery, York immediately wants to turn him in, which his wife opposes.

Fond woman! were he twenty times my son, I would appeach him.

All three ride separately to Henry Bolingbroke in haste. When all arrive begging, Bolingbroke sees ridiculous side (why is it ridiculous that a lord would put public duty before private dynasty? This is the key to the play). York passes the test.

The play ends with Henry Bolingbroke, now Henry IV, trying to draw a line under the bloodshed after rebels have reportedly burnt Cicester and the heads of leading traitors have been severally delivered to him: he spares the Bishop of Carlisle.

Production traditions, and what we can learn from them

Some of the key passages and even scenes I mention here have been edited, downplayed, ridiculed or even entirely omitted from productions I have seen. Rosencrantz's speech, the Yorks' plea to spare their traitor son. Do these puzzle directors, make them confused or uncomfortable? If York is a kind of traitor to the dynastic class, a lord who would sacrifice his own son in the public interest, and York is an extreme exception, and outlier, what does that say about the norms of the English ruling class? Norms that, whatever the background of directors, may have seeped into their conscious and unconscious minds from the conditioning of acceptance to social cheating the Anglo-British establishment specialise in.

Conclusion

We have looked at the phenomenon of bloodsavers in Shakespeare's theatrical works. We see mixed motives in Hector, ambivalence but also humanitarianism in Pericles, false pretence in Henry V, obscurity in Hamlet, tragic conversion to side with innocents far too late in Titus Andronicus, and a number of other characters who do not fit the template one way or another. Only the dramatic character of Edmund of Langley Duke of York (Richard II) passes the test (and only for English lives, not French or Irish) of concern to prevent general bloodshed, even at the cost of his own son's life. A character whose behaviour is so out of keeping with the rest of his social class, we are impelled to look at the character of that class. Because if all characters of a class behave alike in one respect, that behavioural attribute is more likely to go critically unexamined. An exception who, if not proving the rule of the bloodshedding elite, gives compelling evidence for it.

Shakespeare’s Bloodsavers by Sleeping Dog is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.