Abstract

Have you ever watched Macbeth and got the impression there was something else going on in this pre-revolutionary artwork, that was realistically political rather than a magical conspiracy?

Introduction

Is there a case for staging Shakespeare’s Macbeth as a popular uprising, where the witches are not supernatural entities but revolutionaries pretending to be? I think the text supports such a possible reading. If so, how would you stage it? Like this, perhaps. How many changes would it need to the text? None, and possibly a more faithful production is possible and indeed indicated than many contemporary versions. What additions? Mostly dumbshow, to indicate the silent background activity of the revolutionaries, particularly messengers, coordinators, eavesdroppers and common soldiers.

During which explanation, some questions the play raises are answered in this light. I will use ‘revolutionaries’ for the witches’ faction(s), and ‘lords’ as a shorthand to describe the ruling Scottish class including the king, queen, princes, lords, ladies, gentry.

Revolutionaries

The first revolutionaries we see are the three witches, who are rehearsing for their meeting with Macbeth and Banquo. Other revolutionaries are servants, messengers/runners, old folk, camouflaged spies who monitor events. There are ample hints of class war in the text, but also class traitors in the pay of scheming lords.

Witches are (over)acting

The portrayal of the witches should show that they are acting supernatural parts (indeed, sometimes overacting) to con Macbeth (and to some extent Banquo, and indirectly Lady Macbeth) into taking part in their plot. The witches are professional revolutionaries but amateur actors. Hence they only dare appear twice to the most promising mark, Macbeth.

What motivates the witches?

Banquo appreciates this and says as much to Macbeth (enkindle you unto the crown

). But what is the end? Shakespeare will have been familiar with the founding myths of republics such as Rome, whose people apparently kicked out their kings after exposing the rapaciousness of their ruling dynasty. Equally, the witches may be revolting against hierarchical Christianity. This raises the possibility of factions within the revolutionaries, with somewhat different motivations. Clearly, though, the aim is not just to kill any number of kings but to thoroughly discredit kingship amongst the people.

Internecine plot

It seems that the revolutionaries (witches etc) aim to use psychological warfare to ‘enkindle’ the lords into a mutually destructive conflict. They have done their research, but there are factors outside their control or influence (like the English).

Revolution HQ targets and dumb show

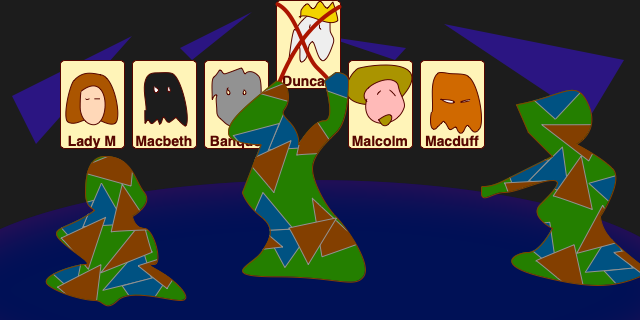

Staging the Revolution will probably require showing a Rebel Headquarters on stage in key scenes, perhaps literally underground compared with concurrent action. This HQ could feature large cards showing Duncan atop row of Malcolm, Donalbain, Macbeth, Lady Macbeth, Banquo, Macduff, perhaps Lenox, Cawdor, Rosse, Menteth, Angus, Cathness or so and such, some crossed out during play, some removed or added?

Class War

There are a number of indications of class war in the text. The word ‘slave’ is used as a pejorative by the lords, while lords are ‘noble’. Servants live in fear of upsetting lords. Something is brewing. Were the kerns and gallowglasses foreign freedom fighters?

Lords

Where are Macbeth’s wounds?

The wounded sergeant spins a tale of Macbeth’s toe-to-toe battlefield heroics, but this is almost immediately rendered implausible. No reference to Macbeth’s wounds are ever made (though some productions choose to show them). Indeed, Macbeth rides furiously home and his wife embraces him without comment on any hurt.

We later find that Macbeth has servants in his pay throughout the lords’ households. If we look at the over-flowery speech of the wounded sergeant, we see he falters after delivering Except they meant to bathe in reeking wounds

as if he realises he has over-delivered on his tale.

Lords lie, use flowery-serpent courtesy.

Malcolm

Malcolm delivers the most devastating critique of hereditary monarchy, so much that Macduff has difficulty processing it.

Cowardice not valour is the norm

Shakespeare mocks the lords’ pretensions to valour, not just in Macbeth (who needs promise of a charmed life to enkindle him, and sends others to do his dirty work) but in his enemies like Macduff, who flees his home and family. We may suspect that common soldiers win the lords’ battle for them (Duncan conspicuously sits out battle). Not all lords are cowards, though, especially if young and seeking martial glory like Siward's son.

Superstition

A weakness of the lords’ position as a ruling class is its irrationality, so perhaps no wonder they turn to superstition. And yet dispense with it when it doesn’t suit (Macbeth: 'Twas a rough night.

)

Commoners

Commoners sometimes mock courtly speech. Only a small minority will be professional revolutionaries, hence their indirect approach. Many commoners will be employed directly (or indirectly, double-paid as spies) by lords. Some are apparently desperate or vicious enough to volunteer to murder children.

Act 1

Scene 1

A meeting and rehearsal of witchy roles.

Scene 2

The ‘bloody man’ (a sergeant) contrasts with apparently unscathed Macbeth and Banquo. His testimony is flowery, therefore either created by lords for lords and rehearsed, or improvised possibly to set up power struggle. The testimonies credit only lords with victories, a second thaneship is merely a prize, not an additional onerous administrative duty.

At the mention of greeting Macbeth with Thane of Cawdor title, a revolutionary runner sets off to tip off Revolution HQ and witch revolutionaries.

Scene 3

Witches improvise (and may be overheard on heath at distance) waiting for Macbeth and Banquo. A revolutionary runner whispers in their ears. The witches’ greeting now improvised with the Thane of Cawdor news. The Revolution are at times literally underground, or camouflaged. Insane root mention may give witches ideas for later meeting.

Scene 4

Nepotism rules.

Scene 5

Attendant may overhear “metaphysical aid”, revolutionary servants may overhear Lady Macbeth, and Macbeth.

look like the innocent flower, but be the serpent under it

Scene 6

Lady Macbeth not sharing praise for hostess duties.

Scene 7

‘divers servants’ may be well placed to overhear.

Act 2

Scene 1

Servants placed to overhear, to project image of dagger.

Scene 2

Servants could produce the noises and voices.

Scene 3

Suggestions that Revolutionaries have been behind some of the night’s omens to put the wind up the lords.

Malcolm: There’s daggers in men’s smiles: the near in blood, the nearer bloody.

Scene 4

Old Man (possible Revolutionary) makes references to lowly birds of prey attacking mighty and internecine horse conflict, feeding lords’ unease.

Act 3

Scene 1

Macbeth: Masking the business from the common eye

Royalty is not only private government, but murderous and deceitful.

Interestingly the Murderers do not directly agree to kill Fleance, something that a Revolution might consider sadly necessary for all claimants.

Scene 2

Again, servants could overhear Macbeths.

Macbeth lists treason’s tools: steel, poison, malice domestick, foreign levy.

Macbeth: Things, bad begun, make strong themselves by ill

is royalty’s recipe. Essentially royals ride a crime wave.

Scene 3

Servant leads Banquo and Fleance, 3rd Murderer joins previous two. Only Banquo is killed by 1st Murderer. Did Servant and 3rd Murderer collude in letting Fleance escape? Is the Revolution reluctant to kill children?

Scene 4

1st Murderer reports Banquo’s killing and Fleance’s escape to Macbeth as Revolution stages a daring set-piece, the Macbeths’ own servants contriving the appearance (only to Macbeth) of the likeness of Banquo’s supposed ghost. No connection between Macbeth and 3rd Murderer is made.

Angles at the table should make it appear from Macbeth’s end that the opposite seat is taken but not from angles to each side.

The back of a servant’s headdress might give the illusion of a bloodied face some distance behind, whilst another servant has placed a cloth over the chair. The illusion should disappear as Lady Macbeth draws close to her husband’s view angle.

Reappears, disappears as obviously designed, marked, rehearsed, reacting to any changes in sightlines.

Macbeth reveals he has a paid servant as his agent and eyes in every Lord’s house, so why not the Revolution a true believer in each too? Maybe the same servant even.

Scene 5

Does Hecate represent a disgruntled self-styled leader or vanguard of the Revolution? Is this stylised magical cant put on to confuse royalist infiltrators?

Hecate: And you all know, security

Is mortal’s chiefest enemy.

Scene 6

The Scottish lords appear too weak to move against an apparent regicide and tyrant, one meaning of Lenox’s Things have been strangely borne

Act 4

Scene 1

Witches prepare for, and be overheard by, Macbeth.

2nd Witch By the pricking of my thumbs, something wicked this way comes

is crying out to be hammily overdone and cackle-ended, inviting rolling eyes from other witches.

Revolutionaries have practised their special effects, probably throw a bit of insane root into the cauldron, and researched Macbeth’s fears, MacDuff’s birth and Dunsinane’s approaches. Ingredients may obviously be unlike their labels or incongruously packaged. The Revolutionaries plan to stir Macbeth into further outrages against lords to bring about internecine conflict. Which works.

Scene 2

Lady Macduff calls her husband’s flight unnatural and a mother wren decidedly more valorous.

He wants the natural touch: for the poor wren, The most diminutive of birds, will fight, Her young ones in her nest, against the owl.

The messenger who brings warning could be a revolutionary, but one who breaks with or keeps policy?

Scene 3

Revolutionaries will follow to the English court but keep quiet during scene. Have they, not just Macbeth, tried to work on Malcolm?

Malcolm may be testing Macduff, but is also laying bare the true nature of kingship. For example:

Malcolm: I grant him bloody, luxurious, avaricious, false, deceitful, sudden, malicious, smacking of every sin that has a name

but claims he will be much worse still. The silently-watching Revolutionaries may nod in agreement.

Lenox: Would create soldiers, make our women fight

this is essentially the Revolutionary plan, although to the end of removing the last lords standing.

Act 5

Scene 1

The waiting gentlewoman and doctor of physick well know that the crimes of their masters are dangerous to report on.

Doctor: Foul whisperings are abroad

presumably some spread by Revolution.

Scene 2

It seems that the Revolutionaries have chosen Dunsinane for Macbeth’s downfall and planned for a host to travel through Birnam Wood, but have they miscalculated on English power? They seem to need foreign aid since Macbeth appears to have admirers even now of his 'valiant fury'. This is the problem with people who expect one monarch or another to rule over them.

Scene 3

It is a bit late for Macbeth to worry about the health of Scotland, having long had what his wife once called the sickness that should attend power.

Scene 4

Clearly, Revolutionaries amongst the soldiery are already prompting Malcolm’s order to camouflage themselves with branches. Like a Lord he wants to take all credit, of course.

Scene 5

The cry of women signify Lady Macbeth’s death. For good measure, the Messenger should be a Revolutionary to describe a moving wood rather than camouflaged troops.

Scene 6

Revolutionaries in Army are surely in contact with those in Dunsinane and are aware their ruse has worked.

Scene 7

Macbeth is now trapped and cannot fly, emerging onto plain before castle.

Macduff expresses pity: I cannot strike at wretched kernes, whose arms are hir’d to bear their staves

Maybe one of the witches was Macduff’s mother’s midwife?

Again Macbeth is exposed as a coward, relying on charmed protection, but fears humiliation by Malcolm and the rabble’s curse

, although probably hasn’t realised that the rabble’s curse has brought him down already.

Malcolm is crowned king after Macduff kills Macbeth, and horror of horror, creates new earls.

Failure of the Revolution to Establish Popular Government

So, on this interpretation, where did the Revolution go wrong? Did they underestimate the Lords’ hydra-like ability to spawn new Lords to replace those killed in this engineered conflict? Or are they waiting until the English are gone? Do they have a narrative to compete with Malcolm’s? What exactly were the witches’ motives? Were the witches pagans, and was the Revolution also against Christianity, or perhaps religious differences split and weakened it? Do the Revolutionaries start wearing identical blue-brown-green triangle-patterned clothing, and end up in separate blue, brown and green factions, each represented by a different witch? The customary division of witches into Maid, Mother and Crone may help here.

Conclusion

The witches may make more sense in the context of the play, Macbeth, as revolutionaries rather than as supernatural beings. They do not possess more knowledge than could be gathered by eavesdroppers and relayed by messengers. Their acts are performances tried out on Macbeth and briefly Banquo. Certain aspects of the play make more sense as part of an orchestrated internecine plot by republican commoners against corrupt lords. Shakespeare’s play Macbeth can be staged as a popular uprising without changing any text, with the addition of some extras like dumbshow and stage directions for the revolutionary faction.

How to stage Shakespeare’s Macbeth as a popular uprising by Sleeping Dog is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.